Interesting rev chal from Cyber Apocalypse CTF 2025. I did spend many many hours on it, but i think it’s so far the most difficult rev chal I’ve solved.

As a forenote, this write up is quite long.

Chal Description #

Malakar placed a spell on you that transported you to the Nether world. The only way to escape is to remember the enchantments of your forefathers, and unleash your ability to blast through Aether gateways…

Files: rev_gateway.zip

Solution #

Control Flow #

Running the binary we are met with the following prompt:

😈 Malakar has blasted you to the 🔥 Nether 🔥 realms! 😈

🙏 The only way to escape is to teleport to the gateways of the Aether 🙏

And fall down into the mortal realm

Recall the ✨ enchantments ✨ of your forefathers:

Where we can then input our enchantment to solve the challenge.

We can get a bit more information from binwalk and file, seems like we’re working with a 32-bit ELF, which I hadn’t seen in any rev chals before. Also note the unix paths. I’m fairly certain that these are here because the ELF is statically linked. And since it’s also stripped, we can use a ghidra GNU plugin later on to name some of the functions.

❯ file gateway

gateway: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, BuildID[sha1]=b3c8c27272891690a3d00aa745165056bd7041e0, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, stripped

❯ binwalk gateway

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 ELF, 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (GNU/Linux)

148 0x94 Intel x86 or x64 microcode, sig 0x08111ca8, pf_mask 0x06, 1CA8-08-11, rev 0xc8ca8, size 4

617988 0x96E04 Unix path: /usr/share/locale

619224 0x972D8 Unix path: /usr/share/locale

633450 0x9AA6A Unix path: /usr/lib/getconf

635128 0x9B0F8 Unix path: /sys/kernel/mm/hugepages

641588 0x9CA34 Unix path: /usr/lib/locale

643556 0x9D1E4 Unix path: /usr/lib/locale/locale-archive

705188 0xAC2A4 ELF, 32-bit LSB processor-specific, (GNU/Linux)

705296 0xAC310 ELF, 32-bit LSB no machine, (SYSV)

Opening up the binary in ghidra gives us a pretty funky decompilation.

void FUN_08049b7c(void)

{

int iVar1;

undefined4 *puVar2;

undefined4 *puVar3;

undefined4 local_1a4 [32];

undefined4 local_124 [33];

undefined4 local_a0 [35];

puVar2 = local_a0;

for (iVar1 = 0x1f; iVar1 != 0; iVar1 = iVar1 + -1) {

*puVar2 = 0;

puVar2 = puVar2 + 1;

}

puVar2 = local_1a4;

for (iVar1 = 0x20; iVar1 != 0; iVar1 = iVar1 + -1) {

*puVar2 = 0;

puVar2 = puVar2 + 1;

}

puVar2 = &DAT_080de860;

puVar3 = local_124;

for (iVar1 = 0x20; iVar1 != 0; iVar1 = iVar1 + -1) {

*puVar3 = *puVar2;

puVar2 = puVar2 + 1;

puVar3 = puVar3 + 1;

}

return;

}

Where is the code 🤔🤔🤔?!?!??

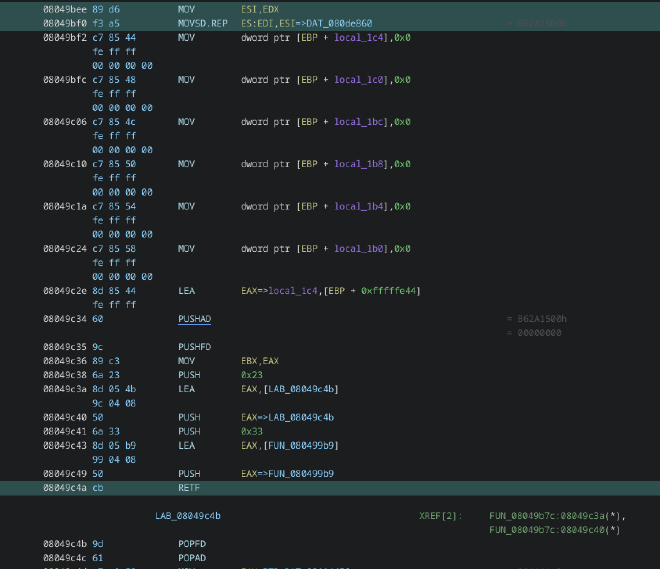

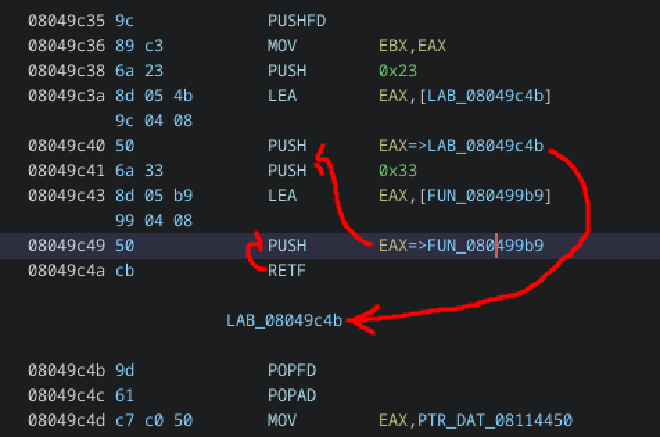

At first glance there doesn’t seem to be any function calls here, but looking at the assembly, we can see that we’re missing some information here.

Return far (retf) is also executed after this, popping the function address off the stack and into the instruction pointer, as well as 0x33 into CS.

Taking a look at that function, it’s even more funky, since it seems to just call another function.

void FUN_080499b9(void)

{

FUN_080497b5();

return;

}

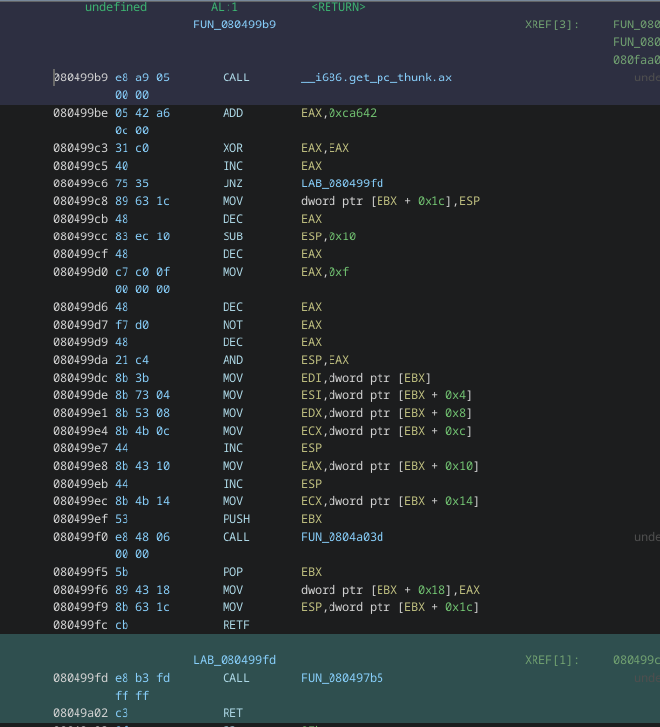

Looking at the assembly tells us more monkey business is going on.

JNZ instruction always jumps to the end of that function because eax should equal 1.

080499c3 31 c0 XOR EAX,EAX

080499c5 40 INC EAX

080499c6 75 35 JNZ LAB_080499fd

080499c8 89 63 1c MOV dword ptr [EBX + 0x1c],ESP

By using a debugger, we can step through the code to see what’s actually happening. When we get to the JNZ instruction, eax actually contains 0, meaning the branch is not taken. This confused me a lot at first, and I realized that I’d just have to deal with it, unsure as to why it was happening (it has to do with CS being set to 0x33).

Now we can see what is actually executing. This asm puts arguments into registers, and then calls FUN_0804a03.

For this solution, this function in particular is not very important to understand, so i’ll skip over it. What is important is the RETF at the end. This ends up popping the first label that was pushed onto the stack into the instruction pointer, and 0x23 into CS.

080499c8 89 63 1c MOV dword ptr [EBX + 0x1c],ESP

080499cb 48 DEC EAX

080499cc 83 ec 10 SUB ESP,0x10

080499cf 48 DEC EAX

080499d0 c7 c0 0f MOV EAX,0xf

00 00 00

080499d6 48 DEC EAX

080499d7 f7 d0 NOT EAX

080499d9 48 DEC EAX

080499da 21 c4 AND ESP,EAX

080499dc 8b 3b MOV EDI,dword ptr [EBX]

080499de 8b 73 04 MOV ESI,dword ptr [EBX + 0x4]

080499e1 8b 53 08 MOV EDX,dword ptr [EBX + 0x8]

080499e4 8b 4b 0c MOV ECX,dword ptr [EBX + 0xc]

080499e7 44 INC ESP

080499e8 8b 43 10 MOV EAX,dword ptr [EBX + 0x10]

080499eb 44 INC ESP

080499ec 8b 4b 14 MOV ECX,dword ptr [EBX + 0x14]

080499ef 53 PUSH EBX

080499f0 e8 48 06 00 00 CALL FUN_0804a03

080499f5 5b POP EBX

080499f6 89 43 18 MOV dword ptr [EBX + 0x18],EAX

080499f9 8b 63 1c MOV ESP,dword ptr [EBX + 0x1c]

080499fc cb RETF

This means that we execute the program like this:

Decompiling the next function looks like this:

void UndefinedFunction_08049c4b(undefined4 param_1,undefined4 param_2,int param_3)

{

undefined4 uStack00000010;

undefined4 uStack00000018;

uStack00000018 = 0;

uStack00000010 = 0x8049c60;

FUN_0805abe0();

uStack00000010 = 0x8049c72;

FUN_08058b00();

uStack00000010 = 0x8049c84;

FUN_08058b00();

uStack00000010 = 0x8049c96;

FUN_08058b00();

uStack00000010 = 0x8049ca8;

FUN_08058b00();

uStack00000010 = 0x8049cba;

FUN_08052700();

*(undefined4 *)(param_3 + -0x1bc) = 0;

*(int *)(param_3 + -0x1b8) = param_3 + -0x9c;

*(undefined4 *)(param_3 + -0x1b4) = 0x80;

*(undefined4 *)(param_3 + -0x1b0) = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(param_3 + -0x1ac) = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(param_3 + -0x1a8) = 0;

return;

}

By looking at the addreess here in uStack000000010, we can determine that FUN_08058b00 is print, meaning we have 4 prints, and then FUN_08052700 is something else (idk, didn’t seem important).

The bottom of this function is also pretty funny looking, values are set on the stack (param_3 is the base pointer as they would for a function call. Turns out the same thing that was in main is also happening here.

08049d01 60 PUSHAD

08049d02 9c PUSHFD

08049d03 89 c3 MOV EBX,EAX

08049d05 6a 23 PUSH 0x23

08049d07 8d 05 18 LEA EAX,[LAB_08049d18]

9d 04 08

08049d0d 50 PUSH EAX=>LAB_08049d18

08049d0e 6a 33 PUSH 0x33

08049d10 8d 05 d5 LEA EAX,[FUN_080498d5]

98 04 08

08049d16 50 PUSH EAX=>FUN_080498d5

08049d17 cb RETF

What it does #

Since this is happening all over the code, I decided to set some fallthroughs in ghidra to make it all one function. Patching the binary probably would’ve been a better choice and would’ve led to a nicer decompilation. My method did not label the function calls, but I knew they were there. Anyways, main ended up looking like this after some labeling that I’ll explain.

void main(undefined param_1)

{

int iVar1;

undefined4 *puVar2;

undefined4 *puVar3;

undefined *puVar4;

undefined4 *puVar5;

undefined4 *puVar6;

int in_GS_OFFSET;

uint auStackY_214 [5];

undefined4 local_1a4 [32];

undefined4 local_124 [26];

undefined4 auStack_bc [6];

undefined4 local_a4;

undefined4 local_a0 [31];

undefined4 local_24;

undefined *puStack_18;

puStack_18 = ¶m_1;

local_24 = *(undefined4 *)(in_GS_OFFSET + 0x14);

local_a4 = 0;

puVar5 = local_a0;

for (iVar1 = 0x1f; iVar1 != 0; iVar1 = iVar1 + -1) {

*puVar5 = 0;

puVar5 = puVar5 + 1;

}

puVar5 = local_1a4;

for (iVar1 = 0x20; iVar1 != 0; iVar1 = iVar1 + -1) {

*puVar5 = 0;

puVar5 = puVar5 + 1;

}

puVar5 = &DAT_080de860;

puVar6 = local_124;

for (iVar1 = 0x20; iVar1 != 0; iVar1 = iVar1 + -1) {

*puVar6 = *puVar5;

puVar5 = puVar5 + 1;

puVar6 = puVar6 + 1;

}

puVar4 = &stack0xfffffe00;

/* IDK WHAT THIS ONE IS*/

FUN_0805abe0(BASE_PROGRAM_ADDR_08114450,0);

/* FUNC_08114068 */

print?((uint *)puVar6[0x1a]);

/* FUNC_080de6a4 MALAKAR PRINT */

print?(puVar6 + -0xd657);

/* FUNC_0x80de740 */

print?(puVar6 + -0xd644);

/* FUNC_080a8de4 */

print?(puVar6 + -0xd630);

/* FUNC_080de768 */

iforgot(puVar6 + -0xd626);

_arg1 = 0;

_arg2 = 0xffffff87;

_arg3 = 0x80;

_arg4 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

_len = _ret_val;

if (_ret_val == 0x21) {

uRamffffffa7 = 0;

_len = 0x20;

puVar4 = &stack0xfffffe00;

/* 0 < 0x21 */

for (_i = 0; _i < _len; _i = _i + 1) {

/* these are the args to the hidden function that gets called, the first arg

here ends up being a pointer to the first input byte i think, since -0x1cc is

0 */

_arg1 = (uint)*(byte *)(_i + -0x79);

_arg2 = 0;

_arg3 = 0;

_arg4 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -4) = 0x23;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -8) = 0x8049dc3;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0xc) = 0x33;

puVar2 = (undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10);

puVar4 = puVar4 + -0x10;

*puVar2 = xor_shift_thing_caller;

*(char *)(_i + -0x79) = (char)_ret_val;

}

*(int *)(puVar4 + -0xc) = _len;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10) = 0xffffff87;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x14) = 0x8049e0c;

shuffleinput(*(char **)(puVar4 + -0x10),*(uint *)(puVar4 + -0xc));

for (_j = 0; _j < _len; _j = _j + 1) {

_arg1 = _j - 0x79;

_arg2 = 1;

_arg3 = 0;

_arg4 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -4) = 0x23;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -8) = 0x8049e7e;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0xc) = 0x33;

puVar3 = (undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10);

puVar4 = puVar4 + -0x10;

*puVar3 = xor_thing_caller;

*(int *)(_j * 4 + -0x179) = _ret_val;

}

is_win = true;

for (_k = 0; _k < 0x20; _k = _k + 1) {

is_win = (*(int *)(_k * 4 + -0x179) == *(int *)(_k * 4 + -0xf9) & is_win) != 0;

}

if ((bool)is_win != false) {

/* 080de7ac => WIN? */

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10) = 0xfffca613;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x14) = 0x8049f1d;

print?(*(uint **)(puVar4 + -0x10));

/* 0811406c => WIN msg 2, something very long idk */

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10) = _DAT_fffffed3;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x14) = 0x8049f2f;

print?(*(uint **)(puVar4 + -0x10));

goto LAB_08049f4a;

}

}

/* 0x80de7f0 => WRONG_ENCHANTMENT080de7f0 */

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10) = 0xfffca657;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x14) = 0x8049f47;

print?(*(uint **)(puVar4 + -0x10));

LAB_08049f4a:

if (_DAT_00000007 == *(int *)(in_GS_OFFSET + 0x14)) {

return;

}

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -4) = 0x8049f5b;

stacksmash();

}

One very important thing to note is that DEC (similarly to INC), also doesn’t actually do anything here, this can also be confirmed by debugging, so a lot of the assembly has decs scattered around, but they don’t do anything and can be ignored.

It’s a little long, but there’s 4 main things it does (bad naming).

xor_shift_thing_caller

This modifies each byte of our input a little bit.

uint FUN_0804a118(void)

{

byte unaff_DI;

return ((unaff_DI) * 2 & 0xaa) | (unaff_DI - 1 >> 1 & 0x55);

}

shuffleinput(*(char **)(puVar4 + -0x10),*(uint *)(puVar4 + -0xc))

Finally a normal function call that doesn’t make me go bananas.

This shuffles the input. Here is the main snippet of what’s happening in it. It gets random numbers from the function somethingelseimportant (mostly not too important), and swaps around values in our already xored input buffer. This produces the same mapping every time.

for (i = 0; i < len; i = i + 1) {

arg1 = 0;

arg2 = 0;

arg3 = 0;

arg4 = 0;

arg5 = 0;

arg6? = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar2 + -4) = 0x23;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar2 + -8) = 0x8049b0e;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar2 + -0xc) = 0x33;

puVar1 = (undefined4 *)(puVar2 + -0x10);

puVar2 = puVar2 + -0x10;

*puVar1 = somethingelseimportant;

swa_idx = out_val % len;

uStack_38 = 0;

tmp = param_1[swa_idx];

param_1[swa_idx] = param_1[i];

param_1[i] = tmp;

}

xor_thing_caller(crc)

This is actually a crc64, but I somehow missed that, and when I tried to implement it in python, I couldn’t get the same output as the binary (if I realized this I likely could’ve solved it a lot faster).

This is actually not very important in my solution, since we end up only caring about the output of it.

for (_j = 0; _j < _len; _j = _j + 1) {

_arg1 = _j - 0x79;

_arg2 = 1;

_arg3 = 0;

_arg4 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

_arg5 = 0;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -4) = 0x23;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -8) = 0x8049e7e;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0xc) = 0x33;

puVar3 = (undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10);

puVar4 = puVar4 + -0x10;

*puVar3 = xor_thing_caller;

*(int *)(_j * 4 + -0x179) = _ret_val;

}

It gets called in this for loop which goes through each byte in our input, and produces an 32-bit integer in a new buffer at a stack offset of -0x179.

- Flag check

This happens in the main function. It goes through each of the 32-bit integers that it just created, and compares them to another constant buffer at an offset of -0xf9.

is_win = true;

for (_k = 0; _k < 0x20; _k = _k + 1) {

is_win = (*(int *)(_k * 4 + -0x179) == *(int *)(_k * 4 + -0xf9) & is_win) != 0;

}

if ((bool)is_win != false) {

/* 080de7ac => WIN? */

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10) = 0xfffca613;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x14) = 0x8049f1d;

print?(*(uint **)(puVar4 + -0x10));

/* 0811406c => WIN msg 2, something very long idk */

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x10) = _DAT_fffffed3;

*(undefined4 *)(puVar4 + -0x14) = 0x8049f2f;

print?(*(uint **)(puVar4 + -0x10));

goto LAB_08049f4a;

}

Getting the Flag #

At first I did try to just implement all this in python and reverse it, but it was not working which confused me for hours.

So I then just went with mapping my input to an output checksum, and then mapping the win buffer back to ascii. The first xor_shift_thing technically doesn’t actually matter overall. What we need to know is how our input is shuffled.

We can read the memory of our input after shuffling, and compare it to our xored input to see how things are shuffled. This looks like this in python (the xor_shift_thing) is easy to implement.

guess = list(b"ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ123456")

# xor_shift_thing_caller

for i in range(0, len(guess)):

b = ((guess[i] * 2) & 0xaa) | ((guess[i] >> 1) & 0x55)

guess[i] = b

# Read from program memory

swapped = [0xa5, 0xa3, 0xa0, 0x85, 0x89, 0x84, 0xa2, 0xa6, 0xa9, 0x87, 0x8b, 0x33, 0x32, 0x8d, 0xa4, 0x83, 0x86, 0xa8, 0x8c, 0x39, 0x82, 0x8a, 0xaa, 0x38, 0x81, 0xab, 0x8f, 0x31, 0x3a, 0xa1, 0x88, 0x8e]

shuf_map = {}

for i, c in enumerate(guess):

shuf_map[i] = swapped.index(c)

print(shuf_map)

# output

# shuf_map = {0: 20, 1: 24, 2: 15, 3: 30, 4: 21, 5: 4, 6: 10, 7: 5, 8: 16, 9: 3, 10: 9, 11: 18, 12: 31, 13: 13, 14: 26, 15: 2, 16: 6, 17: 29, 18: 1, 19: 17, 20: 22, 21: 8, 22: 25, 23: 14, 24: 7, 25: 0, 26: 12, 27: 27, 28: 11, 29: 23, 30: 28, 31: 19}

The next part requires passing in a bunch of different inputs to the program to get they’re checksums, as well as the buffer it should end up being equal to.

Using gdb, we can set some breakpoints when the binary starts comparing things.

The win buffer looks like this. As you can see, values like 0xbfab26a6 repeat multiple times, meaning they’re all the same character.

target = [

0xb62a1500, 0x1d5c0861, 0x4c6f6e28, 0x4312c5a, 0x3cd56ab6, 0x1e6ab55b, 0x3cd56ab6, 0xc06c89b,

0xed3f1f80, 0xbaf0e1e8, 0xbfab26a6, 0x3cd56ab, 0xb3e0301b , 0xbaf0e1e8, 0xe1e5eb68, 0xb0476f7,

0xb3e0301b , 0x3cd56ab6, 0xbfab26a6, 0xe864d8c, 0x4c6f6e28 , 0x4312c5af, 0xb3e0301b, 0x9d14f94,

0xee9840ef , 0x3cd56ab6, 0xbfab26a6, 0xbfab26a, 0x9d14f94b , 0xbaf0e1e8, 0x14dd3bc7, 0x9732958,

0x85a0a3a5, 0xa6a28489, 0x338b87a9, 0x83a48d3, 0x398ca886 , 0x38aa8a82, 0x318fab81, 0x8e88a13

]

And our guess output might will have the same length, but different values.

guess = list(b"ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ123456")

guess_out = [

0xedaefdd5, 0xba6103bd, 0x1186fc89, 0x4fc8314, 0x4f59d312, 0x4c6f6e28, 0xb9c65cd2, 0x464902e,

0xed3f1f80, 0xe788911c, 0xe7197349, 0x3cd56ab, 0x3f7235d9 , 0xb0d68d21, 0xee09a2ba, 0x1807cf2,

0xe42fce73 , 0xee9840ef, 0xb371d24e, 0x6b8b768, 0x1ba09040 , 0xe4be2c26, 0x46d8e0b4, 0x682c29e,

0xb0476f74 , 0x457fbfdb, 0x18962d7a, 0x9495cae, 0xc06c89bf , 0x1221a3e6, 0x4cfe8c7d, 0x1b31721

]

In GDB:

😈 Malakar has blasted you to the 🔥 Nether 🔥 realms! 😈

🙏 The only way to escape is to teleport to the gateways of the Aether 🙏

And fall down into the mortal realm

Recall the ✨ enchantments ✨ of your forefathers: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ123456

Breakpoint 1, 0x08049f0c in ?? ()

(gdb) x/32x $ebp - 0x19c

0xffffbf4c: 0xedaefdd5 0xba6103bd 0x1186fc89 0x4fc83147

0xffffbf5c: 0x4f59d312 0x4c6f6e28 0xb9c65cd2 0x464902e1

0xffffbf6c: 0xed3f1f80 0xe788911c 0xe7197349 0x3cd56ab6

0xffffbf7c: 0x3f7235d9 0xb0d68d21 0xee09a2ba 0x1807cf2f

0xffffbf8c: 0xe42fce73 0xee9840ef 0xb371d24e 0x6b8b768b

0xffffbf9c: 0x1ba09040 0xe4be2c26 0x46d8e0b4 0x682c29e4

0xffffbfac: 0xb0476f74 0x457fbfdb 0x18962d7a 0x9495caed

0xffffbfbc: 0xc06c89bf 0x1221a3e6 0x4cfe8c7d 0x1b317215

Doing this a bunch of times for many different inputs will yield us a map for each checksum and it’s corresponding char. We can also incorporate our shuffle map into this.

guess1 = list(b"ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ123456")

guess_out1 = ...

guess2 = list(b"abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz7890{}")

guess_out2 = ...

guess3 = list(b"!@#$%^&*()_+-=[]\'\":;,.\\|?<>/`~aa") #!@#$%^&*()_+-=[]'":;,.\|?<>/`~aa

guess_out3 = ...

guess4 = list(b"!\"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@") # !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@

guess_out4 = ...

def make_map(guess, expected):

full_map = {}

for (checksum, idx) in shuf_map.items():

full_map[guess_out[idx]] = chr(guess[check_sum])

return full_map

full_map = {}

full_map.update(make_map(guess1, guess_out1))

full_map.update(make_map(guess2, guess_out2))

full_map.update(make_map(guess3, guess_out3))

full_map.update(make_map(guess4, guess_out4))

flag = []

for c in target:

if full_map.get(c):

flag.append(full_map[c])

else:

#flag.append(hex(c))

flag.append('X')

new_flag = ""

new_guess = [''] * 32

for (k, v) in shuf_map.items():

new_guess[k] = flag[v]

print(new_guess)

print(''.join(new_guess))

Flag #

This does end up looking pretty ugly, but after mapping it back, we get the string HTX{r3tf@X_t0_tH3_h3@V3nXg@X3X!}

As you can see by this output, some of the characters are marked by an X, but we are VERY close to the flag. We are missing 5 characters, and we can easily determine that the first is B to make it HTB (Note: I found out the reason for this after the CTF ended, and added it at the bottom of this writeup).

This was super weird, but to looking into it more, it seemed like the outputs would be different based on the position. So I also added the outputs for the reverse of each of our original guesses (read Notes for explanation on this, I was just dumb).

This left us with two unknowns: HTB{r3tf@X_t0_tH3_h3@V3nXg@t3!!}. This is close enough to guess. r3tf@X => r3tf@r, representing the retf instruction in the challenge, which stand for return far. The other part is heavenXgate => heavensgate. In 1337 2p3@k, this could be any of z, s, 2, S, 5.

Testing against the binary tells us it’s 5. Giving us the flag HTB{r3tf@r_t0_tH3_h3@V3n5g@t3!!}

Recall the ✨ enchantments ✨ of your forefathers: HTB{r3tf@r_t0_tH3_h3@V3n5g@t3!!}

ENCHANTMENT CORRECT! YOU HAVE ESCAPED MALAKAR'S TRAP!

Full solution: solution.py

Notes #

I definitely could have gotten this working with no guessing by using something like pwntools to debug the binary and read the crcs for strings made up of only one ascii characters in every position. This should theoretically give a complete map. I’m still not too sure about why the crc is different based on the position though, I was kind of thinking it could be a problem with the debugger and the 32-bit compatability mode interfering somehow? (idk what i’m talking about)

The reason that the solution was not getting the correct crc for each byte was hidden in how I was making python lists out of the GDB output.

Notice that the last column is only 7 hex digits, not 8. This is due to me using a vim macro to convert it to a comma seperated list. This also happened on my guess outputs, so naturally it makes sense that rearranging the guesses would lead to different crcs if the character was mapped at an index where i % 4 == 3. To fix this I can just not chop of the last 4 bits of those crcs.

target = [

0xb62a1500, 0x1d5c0861, 0x4c6f6e28, 0x4312c5a,

0x3cd56ab6, 0x1e6ab55b, 0x3cd56ab6, 0xc06c89b,

0xed3f1f80, 0xbaf0e1e8, 0xbfab26a6, 0x3cd56ab,

0xb3e0301b, 0xbaf0e1e8, 0xe1e5eb68, 0xb0476f7,

0xb3e0301b, 0x3cd56ab6, 0xbfab26a6, 0xe864d8c,

0x4c6f6e28, 0x4312c5af, 0xb3e0301b, 0x9d14f94,

0xee9840ef, 0x3cd56ab6, 0xbfab26a6, 0xbfab26a,

0x9d14f94b, 0xbaf0e1e8, 0x14dd3bc7, 0x9732958,

]

Another note about the nature of the challenge. I’ve read that this ELF is a polyglot, meaning it will execute the same in both x86 and x64. This comes with some side effects like the inc and dec instructions being used to offset instructions to make addressing remain the same in both modes, along with the help of CS=0x33 from retf. Take what I’m saying here with a grain of salt, it’s well explained in the official write up though.